| Citation: | Rui-ping Liu, Fei Liu, Ying Dong, Jian-gang Jiao, El-Wardany RM, Li-feng Zhu, 2022. Microplastic contamination in lacustrine sediments in the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau: Current status and transfer mechanisms, China Geology, 5, 421-428. doi: 10.31035/cg2022030 |

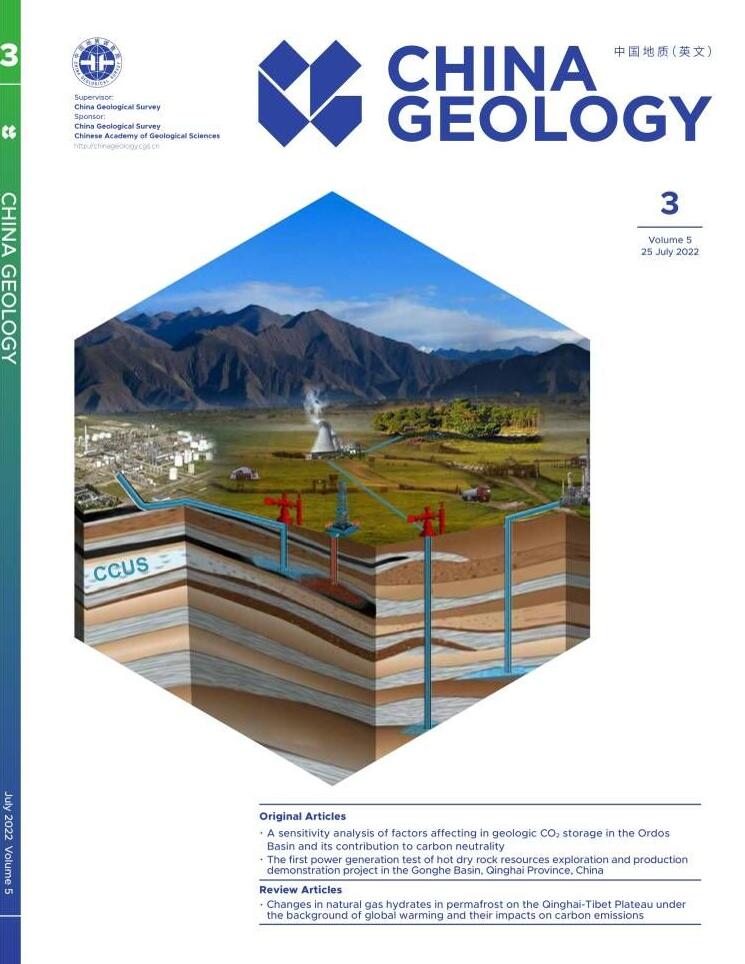

Microplastic contamination in lacustrine sediments in the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau: Current status and transfer mechanisms

-

Abstract

This paper aims to investigate the present situation and transfer mechanisms of microplastics in lacustrine sediments in the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. The study surveyed the average abundance of microplastics in sediments. The abundance of microplastics in sediments of lakes from the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau is 17.22–2643.65 items/kg DW and 0–60.63 items/kg DW based on the data of the Qinghai Lake and the Siying Co Basin. The microplastic abundance in sediments from small and medium lakes is very high compared to that in other areas in the world. Like microplastics in other lakes of the world, those in the lakes in the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau mainly include organic polymers PA, PET, PE, and PP and are primarily in the shape of fibers and fragments. The microplastic pollution of lacustrine sediments in the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau is affected by natural changes and by human activities, and the concentration of microplastics in lacustrine ecosystems gradually increases through food chains. Furthermore, the paper suggests the relevant administrative departments of the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau strengthen waste management while developing tourism and pay much attention to the impacts of microplastics in water environments. This study provides a reference for preventing and controlling microplastic contamination in the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau.

-

-

References

Ahmad M, Li JL, Wang PD, Hozzein WN, Li WJ. 2020. Environmental perspectives of microplastic pollution in the aquatic environment: A review. Marine Life Science & Technology, (4), 414–430. doi: 10.1007/s42995-020-00056-w. Baldwin AK, Spanjer AR, Rosen MR, Thom T. 2020. MPs in lake mead national recreation area, USA: Occurrence and biological uptake. PLoS One, 15(5), e0228896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228896. Biginagwa FJ, Mayoma BS, Shashoua Y, Syberg K, Khan FR. 2016. First evidence of microplastics in the African Great Lakes: recovery from Lake Victoria Nile perch and Nile tilapia. Journal of Great Lakes Research, 42(1), 146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jglr.2015.10.012. Cashman MA, Ho KT, Boving TB, Russo S, Robinson S, Burgess RM. 2020. Comparison of microplastic isolation and extraction procedures from marine sediments. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 159, 111507. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111507. Cheng Y. 2020. Distribution characteristics of perfluoroalkyl substances on estuarine microplastics and gas distribution coefficients on plastics. Guangzhou, Jinan University, Master’s thesis, 1–76 (in Chinese with English abstract). doi: 10.27167/d.cnki.gjinu.2020.000710. Di M, Wang J. 2018. MPs in surface waters and sediments of the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Science of The Total Environment, 616−617, 1620–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.150. Dean BY, Corcoran PL, Helm PA. 2018. Factors influencing microplastic abundances in nearshore, tributary and beach sediments along the Ontario shoreline of Lake Erie. Journal of Great Lakes Research, 44(5), 1002–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jglr.2018.07.014. Dris R, Gasperi J, Saad M, Mirande C, Tassin B. 2016. Synthetic fibers in atmospheric fallout: A source of MPs in the environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 104(1–2), 290–293. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.01.006. Egessa R, Nankabirwa A, Basooma R, Nabwire R. 2020. Occurrence, distribution and size relationships of plastic debris along shores and sediment of northern Lake Victoria. Environmental pollution, 257, 113442. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113442. Fettweis M, Du Four I, Zeelmaekers E, Baeteman C, Francken F, Houziaux JS, Mathys M, Nechad B, Pison V, Vandenberghe N. 2007. Mud Origin, Characterisation and Human Activities (MOCHA). Final Scientific Report, 1–59. Feng SS, Lu HW, Yao TC, Liu YL, Tang M, Feng W, Lu JZ. 2021. Distribution and source analysis of microplastics in typical areas of the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. Acta Geographica Sinica, 76(9), 2130–2141 (in Chinese with English abstract). doi: 10.11821/dlxb202109007. Free CM, Jensen OP, Mason SA, Eriksen M, Williamson NJ, Boldgiv B. 2014. High-levels of microplastic pollution in a large, remote, mountain lake. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 85, 156e163. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.06.001. Gopinath K, Seshachalam S, Neelavannan K, Anburaj V, Rachel M, Ravi S, BharathM, Achyuthan H. 2020. Quantification of microplastic in Red Hills Lake of Chennai city, Tamil Nadu, India. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 27(26), 33297–33306. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-09622-2. Gong F, Han XR. 2020. Analysis of plastic pollution in Qinghai Province and research on prevention and control measures. China Environment, (8), 45–47 (in Chinese). Hu T, Zhang WJ. 2021. New research reveals the characteristics and sources of snow and ice MPs in the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. Xizang Daily, 2021-4-4 (4) (in Chinese). Hossain MS, Rahman MS, Uddin MN, Sharifuzzaman SM, Chowdhury SR, Sarker S, Nawaz CMS. 2020. Microplastic contamination in Penaeid shrimp from the Northern Bay of Bengal. Chemosphere, 238, 124688. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124688. Hu DF, Zhang YX, Shen MC. 2020. Investigation on microplastic pollution of Dongting Lake and its affiliated rivers. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 160, 111555. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111555. Irfan T, Khalid S, Taneez M, Hashmi MZ. 2020. Plastic driven pollution in Pakistan: The first evidence of environmental exposure to microplastic in sediments and water of Rawal Lake. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(13), 15083–15092. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-07833-1. Imhof HK, Ivleva NP, Schmid J, Niessner R, Laforsch C. 2013. Contamination of beach sediments of a subalpine lake with microplastic particles. Current Biology, 23, 867–868. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.001. Jiang CB, Yin L, Li Z, Wen XF, Luo X, Hu SP, Yang HY, Long YN, Deng B, Huang LZ. 2019. Microplastic pollution in the rivers of the Xizang Plateau. Environmental Pollution, 249, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.022. Kataoka T, Nihei Y, Kudou K, Hinata H. 2019. Assessment of the sources and inflow processes of MPs in the river environments of Japan. Environmental Pollution, 244, 958–965. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.10.111. Koelmans AA, Besseling E, Shim WJ. 2015. Nanoplastics in the Aquatic Environment. Critical Review. Marine Anthropogenic Litter, 325–340. Kumar A, Diptimayee B, Sharmila B, Praveen KM, Yadav A, Ambili A, 2021. Distribution and characteristics of MPs and phthalate esters from a freshwater lake system in Lesser Himalayas, Chemosphere, 283, 131132. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131132. Liang T, Lei ZY, Tariful Islam Fuad MD, Wang Q, Sun SC, Fang JKH, Liu XS. 2022. Distribution and potential sources of MPs in sediments in remote lakes of Xizang, China. Science of the Total Environment, 806, 150526. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150526. Liu RP, Xu YN, Zhang JH, Wang WK, El-Wardany RM. 2020. The effect of heavy metal pollution on soil and crops in farmland: An example from the Xiaoqinling Gold Belt, China. China Geology, 3, 403–411. doi: 10.31035/cg2020024. Liu RP, Dong Y, Quan GC, Zhu H, Xu YN, Elwardany RM. 2021a. Microplastic pollution in surface water and sediments of Qinghai-Xizang Plateau: Current status and causes. China Geology, 1, 178–184. doi: 10.31035/cg2021011. Liu RP, Xu YN, Rui HC, El-Wardany RM, Dong Y. 2021b. Migration and speciation transformation mechanisms of mercury in undercurrent zones of the Tongguan gold mining area, Shaanxi Loess Plateau and impact on the environment. China Geology, 2, 311–328. doi: 10.31035/cg2021030. Liu RP, Zhu H, Liu F, Dong Y, El-Wardany RM. 2021c. Current situation and human health risk assessment of fluoride enrichment in groundwater in the Loess Plateau: A case study of Dali County, Shaanxi Province, China. China Geology, 3, 487–497. doi: 10.31035/cg2021051. Liu RP, Li ZZ, Liu F, Dong Y, Jiao JG, Sun PP, El-Wardany RM. 2021d. Microplastic pollution in Yellow River, China: Current status and research progress of biotoxicological effects. China Geology, 4, 585–592. doi: 10.31035/cg2021081. López-Rojo N, Perez J, Alonso A, Correa-Araneda F, Boyero L. 2020. MPs have lethal and sublethal effects on stream invertebrates and affect stream ecosystem functioning. Environmental Pollution, 259, 113898. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113898. Mccormick A, Hoellein TJ, Mason SA, Schluep J, Kelly JJ. 2014. Microplastic is an abundant and distinct microbial habitat in an urban river. Environmental Science & Technology, 48(20), 11863–11871. doi: 10.1021/es503610r. Nel HA, Dalu T, Wasserman RJ. 2018. Sinks and sources: Assessing microplastic abundance in river sediment and deposit feeders in an Austral temperate urban river system. Science of the Total Environment, 612, 950–956. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.298. PlasticsEurope E. 2019. An analysis of European plastics production. Plastics-the Facts 2019. https://www.plasticseurope.org/en/resources/market-data. Su L, Xue Y, Li L, Yang D, Kolandhasamy P, Li D, Shi H. 2016. MPs in Taihu Lake, China. Environmental Pollution, 216, 711–719. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.06.036. Sruthy S, Ramasamy EV. 2017. Microplastic pollution in Vembanad Lake, Kerala, India: The first report of MPs in lake and estuarine sediments in India. Environmental Pollution, 222, 315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.12.038. Thompson RC, Olsen Y, Mitchell RP, Mitchell RP, Davis A, Rowland SJ, John AWG, McGonigle D, Russell AE. 2004. Lost at sea: Where is all the plastic? Science, 304(5672), 838–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1094559. Velasco ADN, Rard L, Blois W, Lebrun D, Lebrun F, Pothe F, Stoll S. 2020. Microplastic and fibre contamination in a remote mountain lake in Switzerland. Water, 12, 2410. doi: 10.3390/w12092410. Vaughan R, Turner SD, Rose NL. 2017. MPs in the sediments of a UK urban lake. Environmental Pollution. 229, 10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.05.057. Van CL, Claessens M, Vandegehuchte MB, Janssen CR, 2015. MPs are taken up by mussels (Mytilus edulis) and lugworms (Arenicola marina) living in natural habitats. Environment Pollution, 199, 10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.01.008. Wang ZB, Li RH, Yang SY, Bai FL, Mei X, Zhang J, Lu K. 2019. Comparison of detrital mineral compositions between stream sediments of the Yangtze River (Changjiang) and the Yellow River (Huanghe) and their provenance implication, 2(2), 169–178. doi: 10.31035/cg2018065. Woodall LC, Sanchez-Vida, A, Canals M, Paterson GL, Coppock R, Sleight V, Calafa A, Rogers AD, Narayanaswamy BE, Thompson RC. 2014. The deep sea is a major sink for microplastic debris. Royal Society Open Science, 1(4), 140317. doi: 10.1098/rsos.140317. Xiong X, Kai Z, Chen XC, Shi HH, Ze L, Chen XW. 2018. Sources and distribution of microplastics in China’s largest inland lake—Qinghai Lake. Environmental Pollution, 235, 99–906. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.081. Yao Z, Li X, Xiao J. 2018. Characteristics of daily extreme wind gusts on the the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, China. Journal of Arid Land, 10(5), 673–685. doi: 10.1007/s40333-018-0094-y. Yuan Y, Wan JH, Wan W. 2016. Analysis on changes for remote sensing in Qinghai-Xizang Plateau lakes during recent 40 years. Environmental Science and Management, 41(10), 8–11 (in Chinese with English abstract). Yuan W, Liu X, Wang W, Di M, Wang J. 2019. Microplastic abundance, distribution and composition in water, sediments, and wild fish from Poyang Lake, China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 170, 180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.11.126. Zhao L, Li W, Lin L, Guo WJ, Zhao WH, Tang XQ, Gong DD, Li QY, Xu P. 2019. Field investigation on river hydrochemical characteristics and larval and juvenile fish in the source region of the Yangtze River. Water, 11(7), 1–20. doi: 10.3390/w11071342. Zhang K, Su J, Xiong X, Wu X, Wu CX, Liu JT. 2016. Microplastic pollution of lakeshore sediments from remote lakes in Xizang plateau, China. Environmental Pollution, 219, 450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.05.048. Zobkov M, Belkina N, Kovalevski V, Zobkova M, Efremova T, Galakhina N. 2020. Microplastic abundance and accumulation behavior in Lake Onego sediments: A journey from the river mouth to pelagic waters of the large boreal lake. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 8(5), 104367. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104367. -

Access History

-

Figure 1.

Map showing the distribution of sampling positions of microplastics in the rivers and lakes of the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. a‒map showing the distribution of previous sampling points; b‒map showing the scope of remote sensing in the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau; c‒ the map of China (The red zone is the study area) .

-

Figure 2.

Migration-transfer patterns and sources of lacustrine MPs in the internal and external ecosystems in the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: